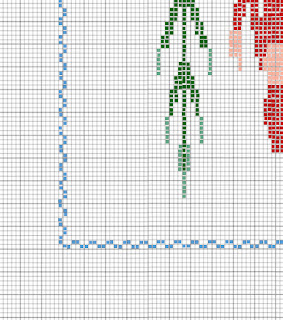

Back around 1980, I was visiting a friend whose family came from Denmark. On her wall was the most charming piece of needlework done in counted cross stitch. She said it was a gift from her aunt and illustrated a popular Danish children's rhyme, En Lille Nisse Rejste (A Little Elf Went Traveling).

A little elf went traveling

By express train, from land to land.

His aim to to meet

The world's biggest man.

He came to the Great Mughal,

Where the giant cabbages grow,

But despite his effort,

No one was so big.

So he went down to the sea

And looked at the clear water;

Then he smiled, for there before him

Was the biggest man in the world.

I often thought of that cross stitch pattern over the years and wished I could find it to do myself. Recently, I googled it again and, lo and behold! It was there, but crammed into a photo with a tea cup and other things. With way too much effort, I managed to transpose the whole thing on to graph paper digitally. Now to actually stitch it! Since that may never happen, I will post this around so others can enjoy it.

Because the pattern is so large, I've divided it up into sections. They do overlap, so take that into consideration.

Here's the tune, if you're interested.

Sunday, November 15, 2015

Friday, November 13, 2015

The Reinvention of Nadezhda Lamanova

I've been reading lately of a Russian fashion designer named Nadezhda (Hope) Lamanova (1861–1941) and wishing I could learn more of her life. She established a strong reputation as a couturier in the early 20th century, designing gorgeous gowns for Empress Alexandra and other members of the Imperial court.

Then came the Russian Revolution. Her position with the court could have very well earned her prison time or cost her her life, but somehow Lamanova reinvented herself as the Dressmaker to the People. There is no starker contrast than that of her lavish court designs and the almost crude patterns she created for the new Russian proletariat.

One reason for the drastic shift was to distance the new regime from the opulence of the Romanovs, but the other was far more practical. The vast majority of Russian women were struggling to feed and clothe their families. There was little reason to design clothing no one would have opportunity to wear; work clothes and one presentable dress was what women needed. Scarcity of fabric was a challenge. Lamanova remembered that in designs that utilized goods women might have on hand: embroidered towels and colorful headscarves. In1925, Lamanova collaborated with sculptor Vera Mukhina to produce a booklet, Art In Daily Life, with extremely simple patterns for sewing garments.

Early in the revolutionary period, women's fashion and home-making magazines were launched, but soon folded, as one source so aptly put it, "for lack of ideas". A Soviet attempt at the Paris fashion show of 1924 was met with much amusement. Because of the lack of luxury fabrics, clothing had been made with anything available, including the rough cotton sacking used to wrap bales.

Despite this, designers like Lamanova were able to inject a small share of fashion into the lives of Soviet women during those very difficult years. Give us bread, and give us roses.

Then came the Russian Revolution. Her position with the court could have very well earned her prison time or cost her her life, but somehow Lamanova reinvented herself as the Dressmaker to the People. There is no starker contrast than that of her lavish court designs and the almost crude patterns she created for the new Russian proletariat.

One reason for the drastic shift was to distance the new regime from the opulence of the Romanovs, but the other was far more practical. The vast majority of Russian women were struggling to feed and clothe their families. There was little reason to design clothing no one would have opportunity to wear; work clothes and one presentable dress was what women needed. Scarcity of fabric was a challenge. Lamanova remembered that in designs that utilized goods women might have on hand: embroidered towels and colorful headscarves. In1925, Lamanova collaborated with sculptor Vera Mukhina to produce a booklet, Art In Daily Life, with extremely simple patterns for sewing garments.

Other women entered the clothing design field, notably Varvara Stepanova, Alexandra Ekster (Exter), and Liubov Popova. One open arena for them was in theater costuming. Theater was a tool for communist propaganda, so lest we imagine costumes for Chekhov or Turgenev, characters were based on stereotypes of groups of strong, identically-dressed workers confronting decadent, flashy, foreign capitalists.

Stepanova, in particular, designed bold, geometric outfits in the Constructivist style.

|

| Stepanova sport suits |

|

| Varvara Stepanova overalls |

|

| Liubov Popova coat sketch |

|

| Alexandra Ekster design |

Early in the revolutionary period, women's fashion and home-making magazines were launched, but soon folded, as one source so aptly put it, "for lack of ideas". A Soviet attempt at the Paris fashion show of 1924 was met with much amusement. Because of the lack of luxury fabrics, clothing had been made with anything available, including the rough cotton sacking used to wrap bales.

Despite this, designers like Lamanova were able to inject a small share of fashion into the lives of Soviet women during those very difficult years. Give us bread, and give us roses.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)